Can osteoporosis cause back pain? Unfortunately, it can be. Understanding why osteoporosis can cause back pain —and what you can do about it — is critical to reclaiming your comfort, quality of life, and mobility.

The starting point is to determine if your osteoporosis is, in fact, the cause of all your back pain. There could be other sources for your discomfort or a combination of sources. We discuss this topic in the next section.

Is Your Back Pain Caused By Osteoporosis?

During my 40 years of clinical practice as a Physical Therapist, I have treated many patients with acute and chronic back pain. I learned that there are many things that can cause back pain.

Before placing the blame on your osteoporosis or osteoarthritis, you should rule out whether the pain is coming from muscles. Without determining that your muscles are the pain source, you shut off all further inquiry and this potentially leaves you with pharmaceutical intervention as your only solution.

Muscles and Back Pain

Back pain from poor posture or compression fractures can occur because of the changes in your spine’s shape—called kyphotic deformity or the “dowager’s hump”. The kyphosis shifts your center of gravity forward. This forces your back muscles to work overtime, contracting constantly to keep you upright. The result? Persistent muscle fatigue and pain that continues even after any initial fracture has healed.

In my practice, I use myofascial release and trigger point massage therapy to both diagnose and treat pain caused by muscle. The best resource, I have found, on trigger point therapy is The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook by Davies and Davies.

They discuss back pain extensively in their book. Davies and Davies state that extreme tension in the deep spinal muscles can entrap the nerve root as it exits the spine and cause pain. (1)

How do you know if the problem is coming from the muscle tension at the spine?

The answer: If a deep spinal muscle is causing the pinched nerve, the muscle will be tight and tender to the touch. A few treatments will improve all the symptoms. However, if the problem is coming from the spine itself, there will be little relief with detailed trigger point massage. The latter indicates that the pain source is not the muscle and likely something else. (1)

To help you evaluate the possible sources of your back pain, I strongly encourage you to work with a clinician with well-trained hands and a good understanding of muscle anatomy.

There are numerous muscles that can be constant sources for back pain. These include deep and superficial spinal muscle, including the longissimus and iliocostalis.

Once you eliminate muscle as the potential source of the back pain, you should consider other sources with your osteoporosis potentially being a culprit. The next section examines how osteoarthritis can be a source of back pain.

Osteoarthritis Back Pain

Osteoarthritis is a normal part of aging, it is the most common type of arthritis of the spine. It is a sign that you have been active and there has been wear and tear (on mostly the facet joints) of your spine. Genetics, diet and lifestyle play a big role in arthritic changes of your spine.

It is more common than not to develop osteoarthritic changes in the spine as we age. Just like osteoporosis, not all individuals with osteoarthritis suffer from back pain.

Here are a few easy ways to determine if your back pain is coming from osteoarthritis:

- Pain is usually associated with stiffness

- Worse with damp rainy weather

- Your spine can predict biometric pressure changes

- You feel more pain and stiffness in the morning or after resting for too long

- Pain and stiffness improves with heat and gentle range of motion exercises

How Osteoporosis Causes Back Pain

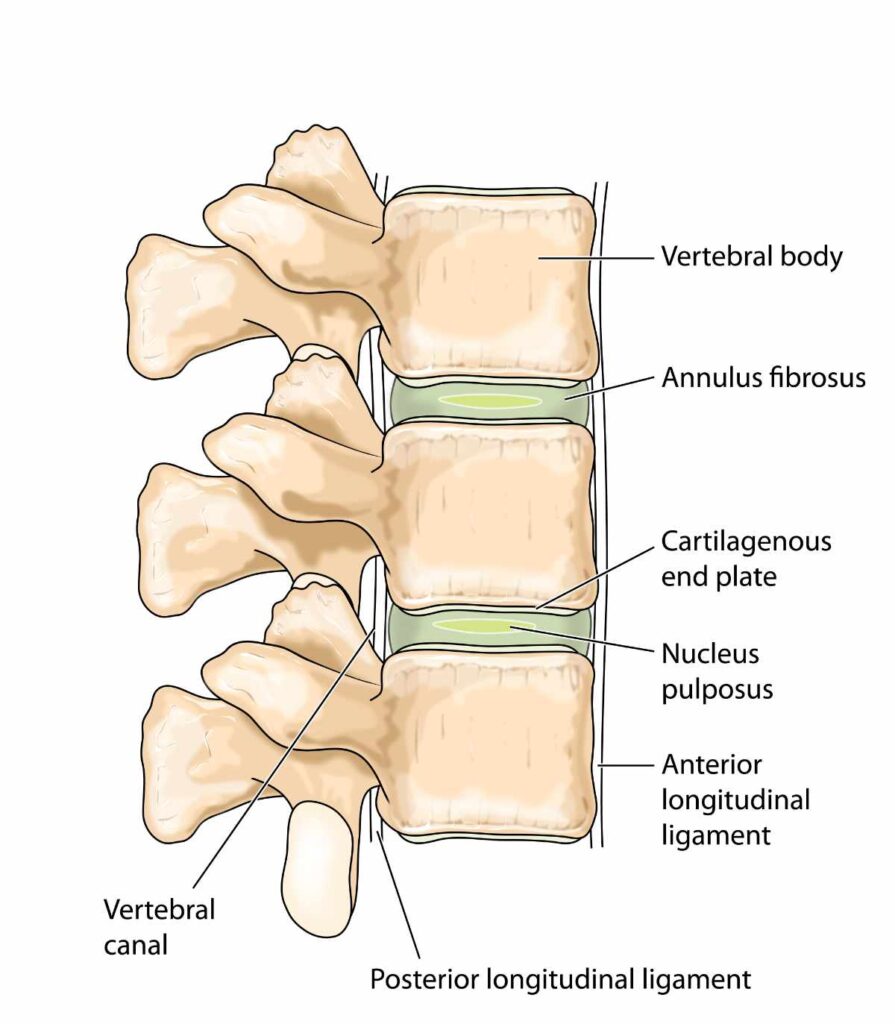

Recent research suggests that the same bone cell imbalances that drive osteoporosis may also contribute to spinal pain through increased osteoclast activity in the vertebral cartilagenous end plates. (2)

Age-related changes in the vertebral cartilagenous end plates (the interfaces between your spinal discs and vertebrae illustrated below) are particularly important. These areas can become porous and develop increased nerve growth, potentially contributing to chronic low back pain.

Osteoporosis Back Pain

Your bones are living, breathing tissues that are constantly rebuilding themselves. In healthy bones, this process, called bone remodeling, is beautifully balanced. But in osteoporosis, this delicate equilibrium gets disrupted in ways that directly generate pain.

The trouble starts with overactive bone-destroying cells called osteoclasts. These cells go into overdrive, breaking down bone tissue faster than your body can rebuild it. The overactive osteoclast don’t just affect the endplates, ask we mentioned above, but can also affect the bone within the vertebra. This process has been shown to create pain generating chemicals.

These chemicals increase the density of pain-sensing nerve fibers within your bones themselves. This means that even minor mechanical stress—like reaching into the back seat of the car or carrying groceries—can trigger significant pain signals. Your bones literally become more sensitive to pain as osteoporosis progresses.

Back Pain After a Compression Fracture

The most devastating consequence of this bone weakening process is vertebral compression fractures. These fractures are incredibly common, affecting an estimated 550,000 to 700,000 Americans every year. Sadly, only about one-quarter to one-third of these fractures are actually diagnosed clinically. (2) Not knowing that you have a compression makes it harder for you to know how to best protect and strengthen your spine.

Roughly half of all vertebral compression fractures can occur with little to no pain. Thus many people are walking around with compressed fractured vertebrae without even knowing it.

Each vertebral fracture sets off a domino effect. Once you’ve had one vertebral fracture, your risk of having another spine fracture increases by five times, and your risk of a hip fracture doubles.

Research shows that vertebral wedging (the most common type of vertebrae compression) averages 21% in people with osteoporosis compared to just 7.7% in healthy individuals. This progressive spinal deformity significantly correlates with back pain severity and can create a devastating impact on quality of life.

Can Osteoporosis Cause Bone Pain?

Recently I spoke to Dr. Keith McCormick and asked him can osteoporosis cause bone pain? Keith explained how bone pain can be caused by the loss of bone density due to inflammation as well as vertebral compression fractures.

Free Osteoporosis Exercise Course

Osteoporosis Pain Management

There are several different types of treatment for osteoporosis pain. We now understand that early, aggressive intervention can significantly improve both pain outcomes and your ability to get through the day. The key is addressing osteoporosis back pain through multiple pathways simultaneously.

Exercise: Your Most Powerful Tool

Exercise interventions have evolved far beyond simple “weight-bearing activities” to sophisticated, multicomponent programs, such as Exercise for Better Bones, that target multiple aspects of bone health. The most effective approach combines moderate-intensity resistance training (at 65-80% of your maximum effort) performed three days weekly with balance work and appropriate weight-bearing activities.

Combined exercise programs consistently outperform single-type exercise approaches. The integration of strength training, balance work, and weight-bearing activities addresses not only bone density but also fall prevention, postural stability, and functional capacity—all crucial for managing osteoporotic back pain.

Balance training deserves special mention. Twelve-month balance programs show significant improvements in balance confidence and meaningful reductions in fall frequency. This is crucial because addressing the psychological fear of falling often helps break the cycle of inactivity that perpetuates bone loss.

Safety is paramount: Certain exercises are absolutely contraindicated if you have osteoporosis, and should be avoided. These include traditional sit-ups, loaded forward flexion (bending forward with weight), and forceful twisting motions. If you’ve had vertebral fractures, you’ll need modified protocols emphasizing extension-based movements with supervised progression. (2)

Nutrition: Beyond Calcium and Vitamin D

While calcium and vitamin D remain foundational—with research confirming that combined supplementation (around 833 mg calcium daily plus vitamin D) produces significant bone density improvements—the nutritional landscape has expanded considerably.

Whole-food approaches consistently outperform isolated supplements. Dairy products fortified with calcium and vitamin D demonstrate superior effectiveness compared to pills alone, while fermented dairy products show additional benefits with 24% hip fracture reduction in observational studies.

Protein adequacy represents a critical but often overlooked component. Optimal intake ranges from 1.0-1.2 grams per kilogram of body weight daily for postmenopausal women and older adults—higher than standard recommendations. High-quality animal proteins show superior outcomes for hip fracture prevention, though combining plant and animal proteins optimizes overall bone health.

The micronutrient profile now includes magnesium (320-420 mg daily) and vitamin K2 (90-120 mcg daily). Nearly 45% of Americans show magnesium deficiency, which impairs calcium utilization and bone formation. Vitamin K2, particularly the MK-7 form, activates osteocalcin for optimal calcium binding to bone matrix. (2)

Modern Pharmaceutical Approaches

While many people, understandably, have reservations about using osteoporosis medications, recent advances have revolutionized how we approach osteoporosis back pain treatment.

Bone-building medications (called anabolic therapies) now outperform traditional bone-preservation (bisphosphonate) drugs for immediate pain relief. (2)

- Romosozumab (Evenity) leads the field for rapid back pain relief, with its unique dual action of increasing bone formation while decreasing bone breakdown. Clinical improvement typically begins within 2-3 months, making it particularly effective for people with acute vertebral fractures. (2)

- Teriparatide remains highly effective, especially when given daily rather than weekly. This pure bone-building medication improves the internal scaffolding of bones (trabecular connectivity) and reduces tiny fracture risk, typically providing pain relief within 3-6 months. (2)

- Denosumab (Prolia) has emerged as the preferred option for people who’ve already experienced fractures, effectively preventing new fracture-related pain episodes through its potent bone-preservation action. (2)

Conclusion

The management of osteoporotic back pain has evolved from reactive treatment to proactive, multimodal strategies. The evidence clearly demonstrates that early intervention with bone-building therapies, combined with appropriate exercise and nutritional strategies, can significantly improve both pain outcomes and functional capacity.

For acute vertebral fractures, bone-building medications provide superior pain relief compared to traditional bone-preservation drugs, with clinical improvement typically beginning within 2-3 months. This should be followed by transition to bone-preservation therapy to maintain gains.

Your exercise prescription should emphasize multicomponent programs with professional supervision, especially during initial phases. Nutritional interventions require comprehensive approaches that go well beyond basic calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

The prognosis for osteoporotic back pain has improved significantly with these evidence-based approaches, particularly when implemented early in the disease process. Coordinated care that addresses the biological, mechanical, and psychological aspects of osteoporotic fracture management can substantially improve quality of life outcomes and reduce the devastating impact of progressive spinal deformity.

Remember: osteoporotic back pain is complex, but it’s not hopeless. With the right combination of treatments, many people experience significant improvement in both pain and function. The key is working with healthcare pro

Margaret Martin

Further Readings

References

- Davies C., Davies A. The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook. 3rd ed. New Harbinger Publications Inc. 2013.

- Zhen, G., Fu, Y., Zhang, C. et al. Mechanisms of bone pain: Progress in research from bench to bedside. Bone Res 10, 44 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-022-00217-w

Comments